- Sep 8, 2025

Making Sense of a Co-Citation Network

- Chaomei Chen

- 0 comments

9/8/2025

A co-citation network is a rich source of inspirational insights, intriguing connections, maybe even transformative surprises. A large enough co-citation network is necessarily complex structurally, temporarily, and above all, intellectually. Overtime, layers, patches, as well as new branches of networks would emerge and morph into existing ones. What can we learn from the duality of a co-citation network and its citing articles? How would our newly learned lessons alter our understanding of how a research field finds its own way ahead with competing as well as encouraging lights shed from a diverse spectrum of independent and creative minds?

Here I’d like to share a few examples of how one can make sense of an extended type of co-citation network. Traditionally, when we analyze a co-citation network, the attention is primarily focused on what has been cited. A more holistic question on what has been cited by whom in what context is largely in the sideline.

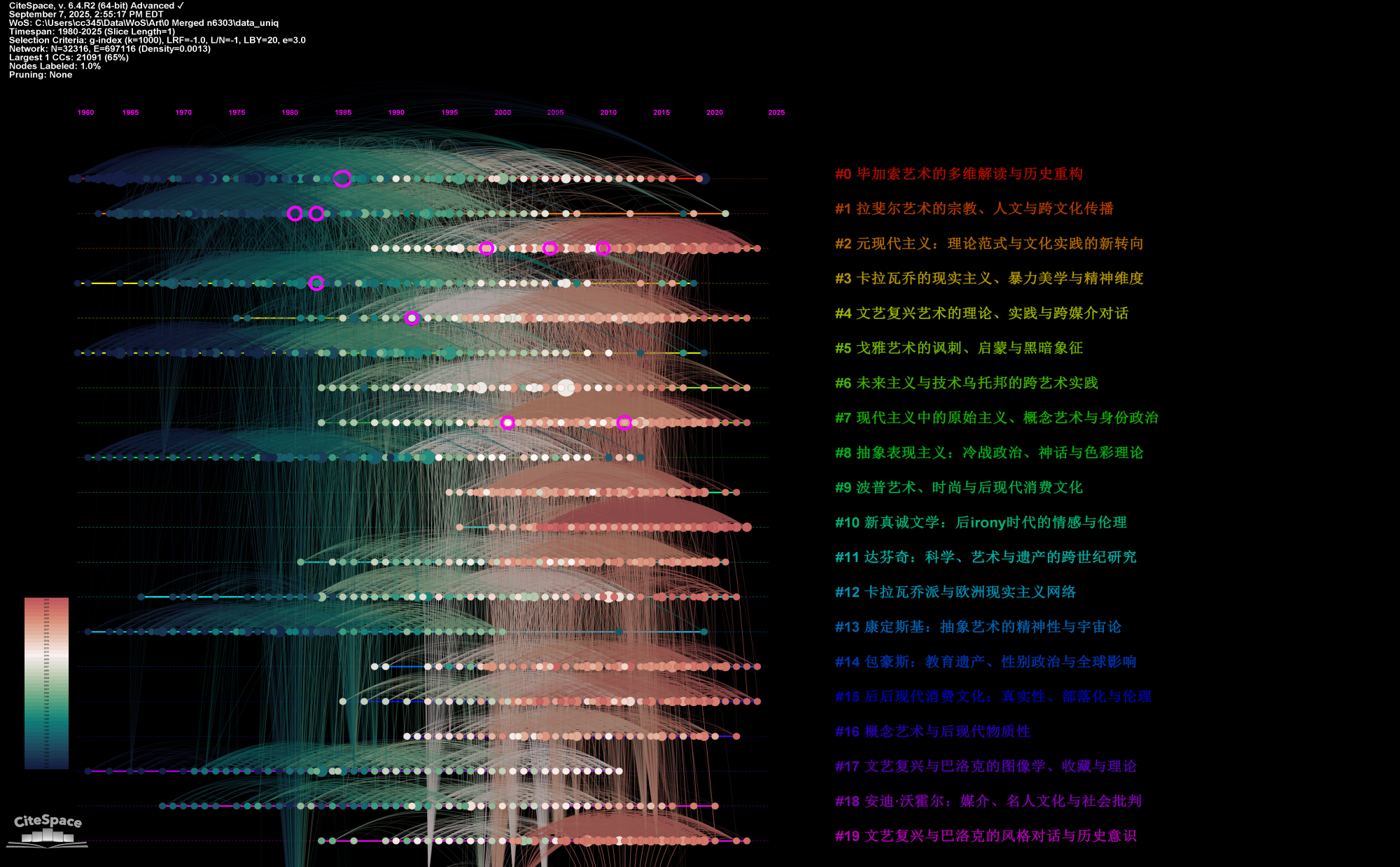

Let’s start with some important properties of a co-citation network. As with any large network, the large connected component is usually the center of the analysis. As you can see in the following example, the large connected component is where the most interesting things take place. It has a rich structure. It is also dynamic, which means if you take a look at it at difference times, you may see significant changes in its structure sometimes as well as relatively stable structure in other times. In this blog, I used a dataset of art literature for the numerous rises, falls, spirals, and come-backs of different kinds of techniques, styles, appreciations, and critiques. The entire network features 100,168 cited references and 131,845 co-citation links. The numerous singleton nodes floating around the center stage are conventionally outside the scope of our concern.

Here is the largest connected component of a hybrid network of keywords and cited references with the same dataset. The entire network has 102,397 nodes and 135,022 edges. Its largest connected component has 28,241 nodes (27% of the entire network).

Given a network, an effective way to make sense of it is to work with its structure at an intercluster level. How is the network organized in terms of clusters? What are these clusters about and how are these clusters connected?

In my 2004 PNAS paper, I conceptualized the importance of the notion of duality in understanding co-citation networks. The duality means that we should bear in mind the tension between the cited references and their citing articles. In some situations, citing articles may share the same contexts with the cited references, whereas in other situations, citing articles may transcend the original contexts of cited references. As such, we may end up with two distinct explanations of what a cluster is really about. We have one when we focus on the footprint or the shadow on the sandy beach. We can have another one when we focus directly on the creature that generated the footprint or the shadow in the first place. Both are supported in CiteSpace. Some users asked me how come a cluster’s label does not seem to capture what they expected based on the cited references. There was a short story. A school teacher asked her class of students to look at a picture of the feet of a bird and tell what kind of bird the feet belongs to. One student felt helpless and he tried to leave the classroom. His teacher stopped him and asked for his name. The student quietly put up his feet as his answer for the teacher, or rather as an exercise for the teacher. In CiteSpace, the default source of what a cluster is about is the citing articles. It departures from the traditional analysis of a co-citation network. Not only are we interested what have been cited, but also in what contexts they are cited.

More about the role of LLMs in cluster summarization shortly.

Look Back Years

One of the reasons why a large co-citation network may be tangled to a dense hairball is due to exceedingly long-range links, i.e., a 20th century research article cited a 19th century publication. CiteSpace allows users to control such long-range links, for example, no more than 20 years, by setting the Look Back Year (LBY) parameter. The LBY parameter improves the clarity of the latent progressive movements.

Once we break down a network to a stream of clusters. There are obviously two ways to traverse the network through clusters: 1) starting from the largest cluster and moving in descending order of the cluster size. This approach focuses on the most influential clusters first. 2) starting from the earliest clusters and moving through clusters in chronological order. As such the two options guide us to navigate through the network.

Traverse the network by cluster size:

Traverse the network in chronological order:

Clusters Summarized

LLMs provide a valuable resource for facilitating our understanding of a cluster. CiteSpace taps on gpt-4o, gpt-4-mini, and deepseek for cluster summarization so that we can make sense of the nature of a cluster by simply reading a paragraph of a summary along with a list of keywords to highlight multiple dimensions that may characterize a cluster.

Here I include the summaries of the largest 12 clusters to illustrate how these summaries combine thematic highlights along with specific publications as an expert would write in their narrative reviews of the relevant literature. The source data was in English. I intentionally chose a different language for cluster summarization.

The largest 5 clusters all have over 1,000 references each. The largest cluster Cluster #0 has 1,838 references. The smallest cluster among them as 465 (Cluster #11).

The average age of a cluster gives us some idea when it was essentially formed or peaked. A few clusters had their high time in early 1980s. Similarly, a few clusters were concentrated around 2012. From the landscape view and the timeline view below, we can easily tell which cluster was formed most recently and which one emerged first.

The following cluster summarization was generated in CiteSpace in Chinese. If you are interested in the details, you may translate them to your own language using ChatGPT or a similar LLM tool.

Cluster #0: 毕加索艺术的多维解读与历史重构

Summary: 本集群聚焦于毕加索艺术的深度解析,涵盖其立体主义创新、政治意识形态表达、战争影响及跨文化对话。代表性研究主题包括《亚维农的少女》的哲学阐释(Florman 2003; Gedo 1980)、立体主义与战争政治的关联(Leighten 1985; Cottington 1988)、西班牙内战对作品的影响(Burgard 1986; Calvoserraller 1981),以及古典传统与原始主义的融合(Denti 1986; Chave 1994)。新兴趋势涉及性别与种族议题的批判性重读(Lubar 1997; Chave 1994),争议观点围绕精神分析解读与历史叙事的有效性(Gedo 1981; Johnson 1980)。方法论上结合形式分析、社会史与后殖民理论,揭示了毕加索作为文化符号的复杂性和现代艺术史的建构过程。

Keywords: 毕加索;立体主义;《亚维农的少女》;政治艺术;跨文化影响

Cluster #1: 拉斐尔艺术的宗教、人文与跨文化传播

Summary: 本集群深入探讨拉斐尔艺术的宗教象征、人文主义理想及其在欧洲的接受史。核心主题包括梵蒂冈宫壁画的神学与哲学内涵(Brilliant 1984; Varanelli 1983)、祭坛画的仪式功能与图像学(Cooper 2001; Caron 1988),以及北方艺术与古典遗产的影响(Quednau 1983; Passavant 1983)。研究强调拉斐尔对古代艺术的复兴(Cohen 1984)与建筑理论的贡献(Rowland 1994),并分析其作品在荷兰等地的传播机制(Vanadrichem 1992; Vanadrichem 1994)。方法论上融合了文献考据、风格分析与接受美学,揭示了文艺复兴艺术作为文化对话媒介的角色。争议点涉及特定作品如《圣母加冕》的阐释分歧(Vonteuffel 1987; Stefaniak 2000)。

Keywords: 拉斐尔;文艺复兴;宗教艺术;古典复兴;跨文化传播

Cluster #2: 元现代主义:理论范式与文化实践的新转向

Summary: 本集群系统探讨元现代主义(metamodernism)作为后现代之后的文化逻辑,涵盖哲学、文学、艺术与社会实践。核心议题包括振荡(oscillation) between现代性与后现代性(Vermeulen 2010; Gibbons 2019)、新真诚(new sincerity)的美学政治(Adiseshiah 2016; Kelly 2024),以及数字时代的主体性重构(Jordan 2024; Radchenko 2025)。研究连接了俄罗斯反对派音乐(Morozov 2024)、时尚设计(Gerrie 2020)与城市水系统(Franco-torres 2021),强调跨学科方法(Pipere 2022)和全球伦理叙事(Corsa 2018)。方法论上采用话语分析与文化研究,争议点围绕元现代主义是否真正超越后现代(Bentley 2018),及其与解构主义、新现实主义的关系。

Keywords: 元现代主义;后现代之后;振荡;新真诚;数字文化

Cluster #3: 卡拉瓦乔的现实主义、暴力美学与精神维度

Summary: 本集群聚焦卡拉瓦乔艺术的革命性现实主义、宗教情感表达及其生平争议。主要研究主题包括光暗对比(chiaroscuro)的戏剧性运用(Thomas 1985)、暴力与牺牲的视觉化(Varriano 1999; Stone 1997),以及自传性元素与精神危机(Burgard 1986; Gedo 1981)。新兴分析涉及手势符号学(Poseq 1992)与北方欧洲影响(Causa 1999),争议点围绕《以撒的笑》等作品的题材识别(Rudolph 2001)。方法论结合技术分析(如X射线检测)、社会史与心理分析,揭示了巴洛克早期艺术与反宗教改革文化的交织。

Keywords: 卡拉瓦乔;现实主义;宗教艺术;暴力表现;巴洛克

Cluster #4: 文艺复兴艺术的理论、实践与跨媒介对话

Summary: 本集群考察文艺复兴艺术的理论建构、技术实践及其与文学、科学的互动。核心主题包括阿尔伯蒂与库萨的视觉认识论(Carman 2014)、米开朗基罗的未完成美学(Carabell 2014),以及拉斐尔与北方文艺复兴的交流(Baldriga 2021)。研究强调艺术与人文主义的共生(Biow 2018),如但丁与彼特拉克对绘画的影响(Reilly 2010),以及素描与印刷文化的角色(Viljoen 2001)。方法论上融合观念史、物质文化与技术研究,争议点涉及“原始派”收藏的意识形态(Collier 2017)。

Keywords: 文艺复兴理论;视觉文化;人文主义;跨媒介;技术实践

Cluster #5: 戈雅艺术的讽刺、启蒙与黑暗象征

Summary: 本集群分析戈雅艺术的讽刺性、社会批判与潜意识探索。代表性研究聚焦《狂想曲》的感官政治(Schulz 2000)、战争灾难的伦理视觉(Shaw 2003),以及寓言与 emblematic 传统(Moffitt 1987; López Vázquez 1985)。主题包括启蒙理性与非理性的张力(Klein 1998)、性别与权力的表现(Tomlinson 1991),以及技术如版画的语言创新(Vega 1995)。方法论结合图像学、精神分析与历史语境化,争议点围绕《农神吞噬其子》的学术批评(Poeschel 1997)。

Keywords: 戈雅;讽刺艺术;启蒙运动;战争描绘;版画

Cluster #6: 未来主义与技术乌托邦的跨艺术实践

Summary: 本集群探索未来主义对机器、速度与广播技术的乌托邦想象及其政治矛盾。核心议题包括马里内蒂的无线电美学(Fisher 2009)、舞蹈与身体机械化(Veroli 2009),以及全球现代主义的权力地理(Mitter 2014)。研究揭示未来主义与无政府主义、法西斯主义的复杂关系(Berghaus 2009),及其在芭蕾(Gaborik 2011)和珠宝设计(Bliss 2019)中的遗产。方法论采用媒介理论与政治哲学,争议点涉及技术乐观主义与焦虑的并存(Berghaus 2009)。

Keywords: 未来主义;技术乌托邦;媒介实验;政治意识形态;身体美学

Cluster #7: 现代主义中的原始主义、概念艺术与身份政治

Summary: 本集群审视现代主义中的原始主义话语、概念艺术转向与后殖民批判。重点研究包括毕加索《亚维农的少女》的非洲摄影来源(Cohen 2015)、概念艺术与工艺的交叉(Corey 2016),以及制度批判(Kalcic 2023)。分析涉及超现实主义与达达的遗产(Allan 2011)、性别与queer理论(Schiff 2024),以及全球艺术史的方法论挑战(Elkins 2015)。方法论上结合后殖民理论、物质文化与档案研究,争议点围绕1984年MoMA“原始主义”展览的批评(García 2024)。

Keywords: 原始主义;概念艺术;后殖民批评;身份政治;全球现代主义

Cluster #8: 抽象表现主义:冷战政治、神话与色彩理论

Summary: 本集群探讨抽象表现主义的意识形态、心理维度与形式创新。核心主题包括冷战时期的文化外交(Hills 1984; Jachec 2003)、神话与原始主义的回归(Langhorne 1989; Zucker 2001),以及色彩的情感与精神性(Gibson 1981; Firestone 1981)。研究批评其欧洲中心叙事(Craven 1991),并分析自动化与无意识创作(Craven 1990)。方法论融合社会艺术史、精神分析与形式主义,争议点围绕艺术与政治动员的关系(Zucker 2001)。

Keywords: 抽象表现主义;冷战文化;神话重构;色彩理论;自动化

Cluster #9: 波普艺术、时尚与后现代消费文化

Summary: 本集群分析波普艺术与时尚、消费文化的互文性及其 queer 政治。主要研究包括沃霍尔的工厂美学(Sichel 2018; Kass 2018)、时尚的元现代转向(Gerrie 2020),以及注意力经济(Reilly 2019)。主题涉及机械复制与欲望(Maizels 2014)、舞蹈与身体政治(Aramphongphan 2021),以及概念艺术的限量版本(Vogel 2024)。方法论采用文化研究、酷儿理论与媒介考古,争议点围绕波普的批判性与共谋(Sichel 2018)。

Keywords: 波普艺术;消费文化;时尚理论;queer 政治;机械复制

Cluster #10: 新真诚文学:后irony时代的情感与伦理

Summary: 本集群考察新真诚(New Sincerity)作为后后现代文学的核心范式,聚焦情感转向、伦理承诺与 neoliberalism 批判。代表研究包括大卫·福斯特·华莱士的《无尽的玩笑》(Bartlett 2016; Lambert 2020)、珍妮弗·伊根的类型转向(Kelly 2021),以及Zadie Smith的《NW》(Bentley 2018)。主题涉及irony的悬置(Doyle 2018)、自传体小说(Gutiérrez 2024),以及全球小说中的身份(Nicol 2019)。方法论结合叙事学、情感理论与政治哲学,争议点围绕新真诚与neoliberalism的共谋(Lambert 2020)。

Keywords: 新真诚;后现代之后;情感转向;伦理叙事;neoliberalism

Cluster #11: 达芬奇:科学、艺术与遗产的跨世纪研究

Summary: 本集群多维解读达芬奇的科学与艺术实践,及其理论遗产。核心主题包括《绘画论》的传播与影响(Farago 2018; Tempesti 2010)、解剖学与自然研究(Mare 2019; Bernardoni 2014),以及技术如颜料分析(Zumbuehl 2009)。研究强调其跨学科方法(Veltman 2008),与拉斐尔、米开朗基罗的对话(Joannides 2005),以及现代博物馆学中的展示(Gobbato 2022)。方法论结合手稿研究、科学史与保护科学,争议点涉及作品真伪与阐释历史。

Keywords: 达芬奇;科学与艺术;《绘画论》;解剖学;遗产研究

Optimized Layout

Landscape View

With a landscape view, we can easily find which cluster emerged first, whether a cluster is diminished, how long did it last, and which clusters are currently going strong and what they are about.

For example, although Cluster #0 is the largest cluster, it is no long a significant player in the most recent years. In contrast, Clusters #2 and #10 are going strong, while Clusters #4 and #7 are reaching their final stage.

Timeline view

Nodes with purple rings are the ones with strong betweenness centrality scores. In theory, such as the Structural Hole Theory and my own Structural Variation Theory, they are the candidates for potentially significant bridges between different schools of thought. They hold the key to a profound understanding of not only one single cluster but multiple interconnected clusters.

If you have any questions or comments, please leave a message in the comment section.